Eugenio Zuccarelli and Fernanda de Araujo

Background

How climate change is impacting millennial winos and To invest in Wine, Invest in Climate Change

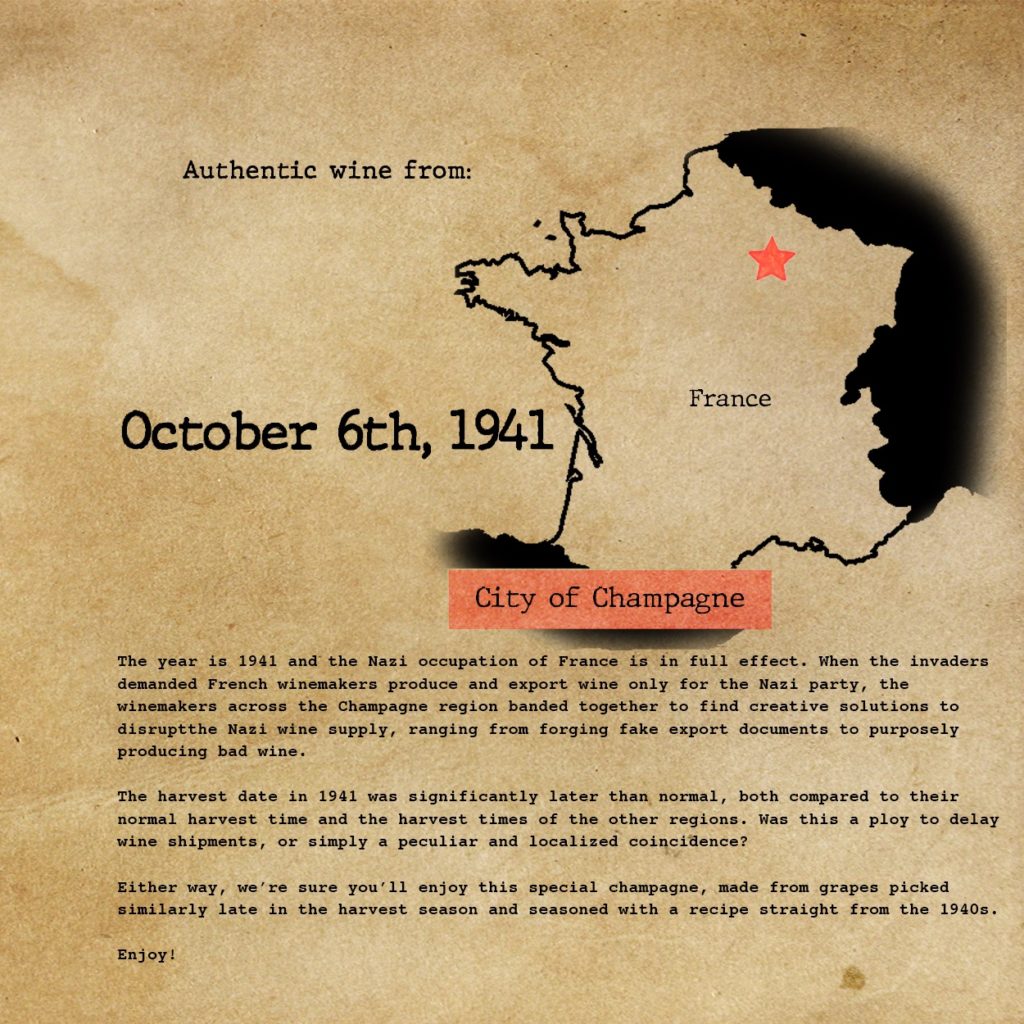

For our re-imagined project, we used the Instagram video format from Olivia and Smara’s “millennial winos” sketch and the advocacy angle of Eugenio, Tyler and Neil’s “To Invest in Wine, Invest in Climate Change” sketch. We created a full 1-minute Instagram video, with stock photos and videos of people drinking wine, vineyards as well as images associated with climate change. We also interviewed Valeria Ricci from La Mesma winery in Italy, through Zoom, and used short clips from the interview throughout the video. We used an eerie soundtrack that is both reminiscent of such Instagram videos and signifies the danger wine production is in due to climate change.

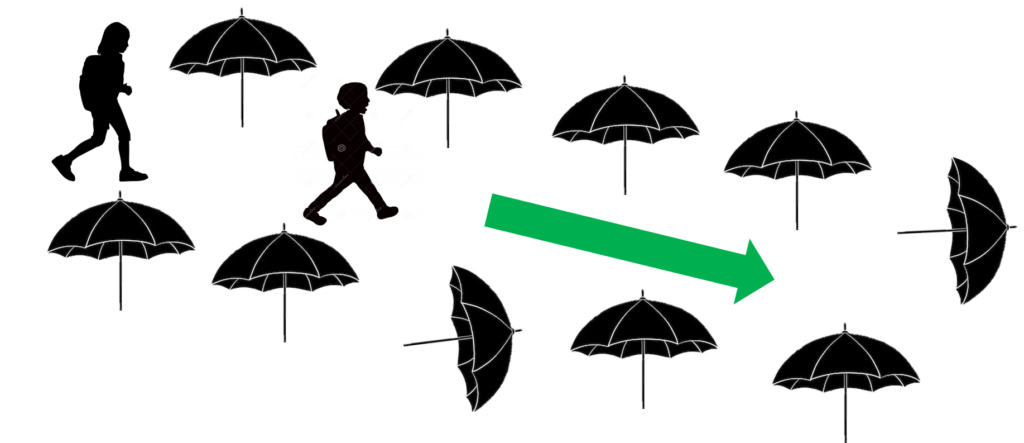

Because this is an Instagram video, our audience is social media users, especially those in their 20s and 30s. The images used in the video are of young people enjoying wine in social settings, so we hope viewers will see themselves in the images. Our main goal was to alert wine consumers in their 20s and 30s to this very real impact of climate change and galvanize them to take action.

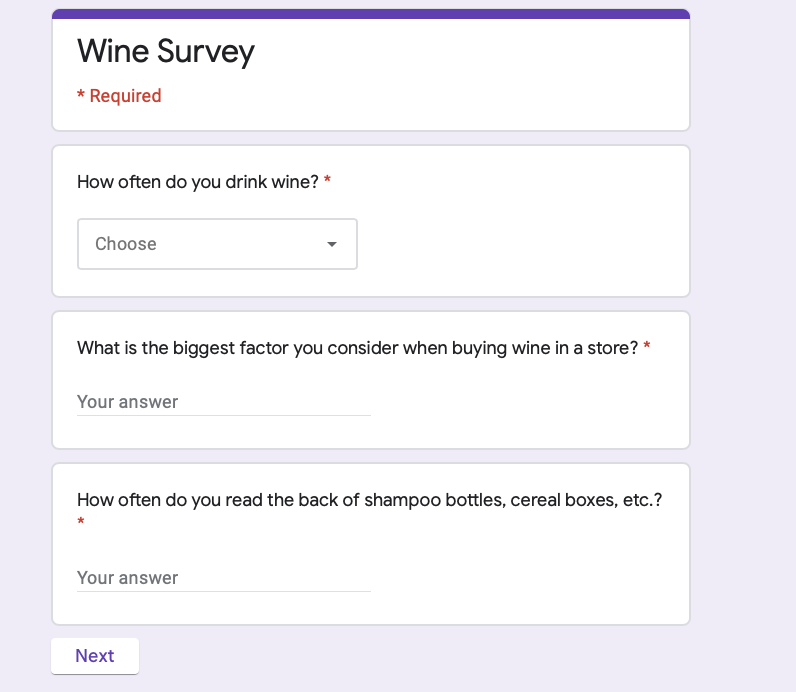

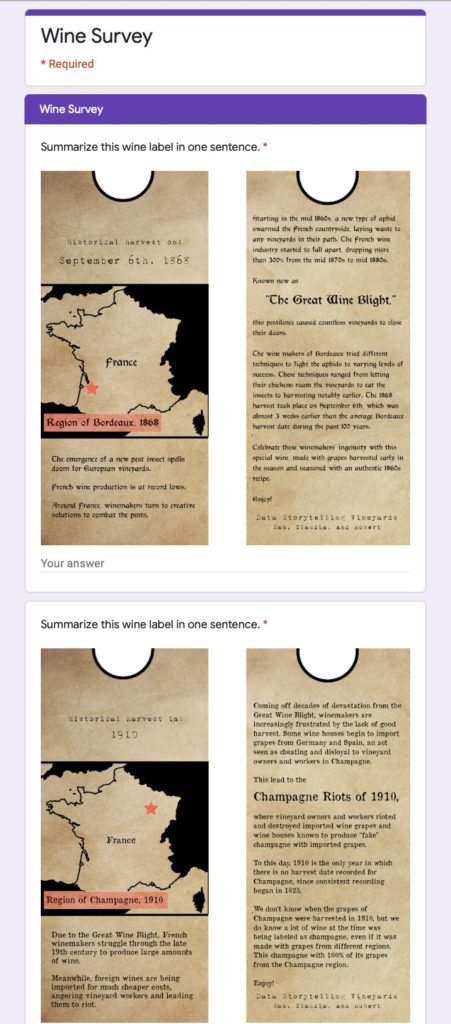

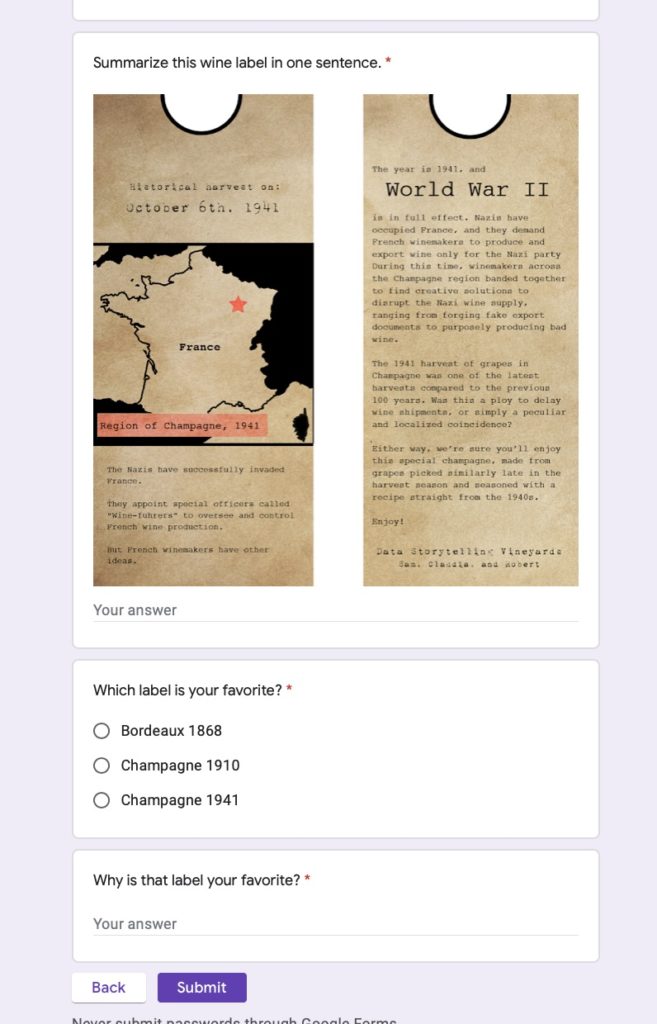

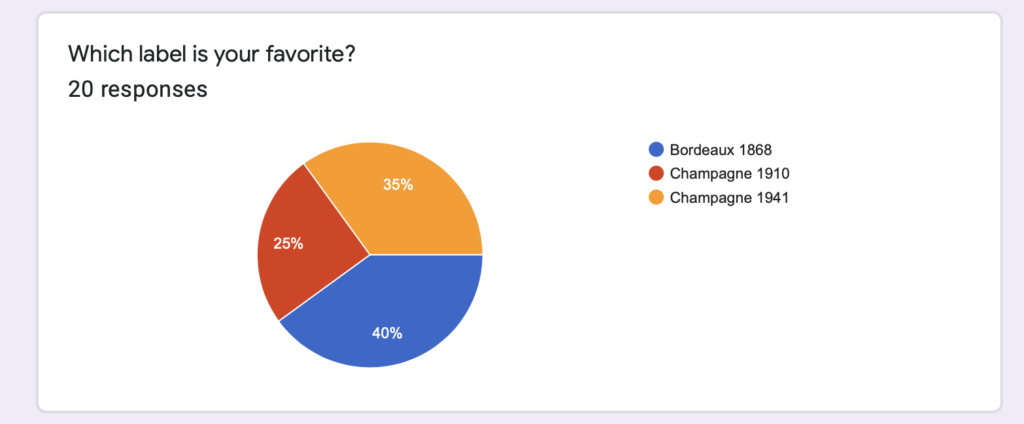

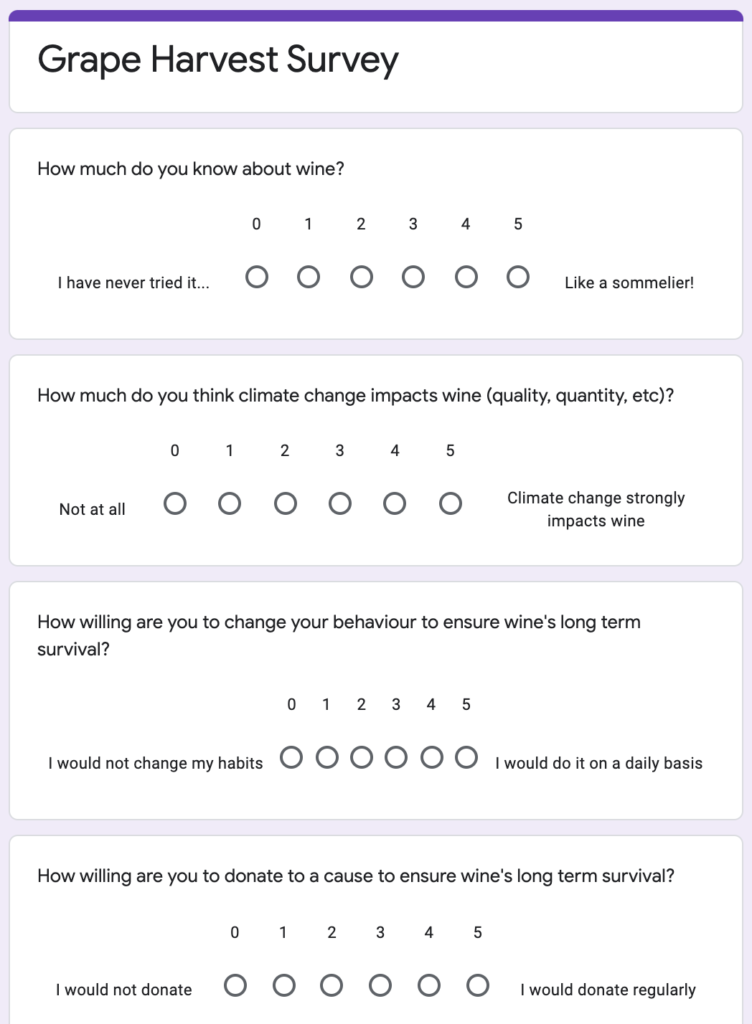

For our impact assessment, we focused primarily on investigating whether the video changed viewers willingness to pursue climate change action, such as donating to climate change funds and changing their personal behavior. We generated a Google Form that asked viewers 4 questions (one assessing previous knowledge about the issue and the rest o evaluate the base willingness to take action), had them watch the 1-minute video, and asked 3 follow-up questions to see if they were more likely to change their actions now. We also shared the video on Instagram and saw how it performed in the first 24 hours.

Google Form: https://forms.gle/aBC2pPLDsbSQzGjT6

Results

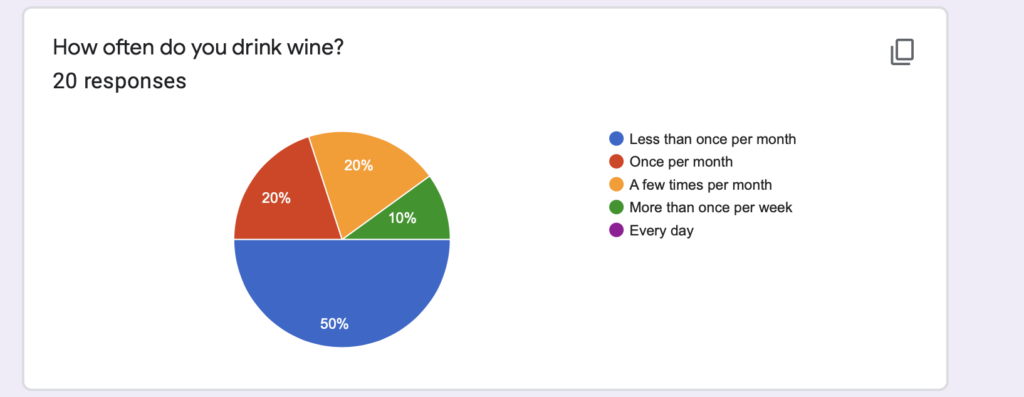

We shared the form with audiences in their twenties but without restricting to only wine connoisseurs at the beginning. By doing so, we were then able to collect more responses, and assessing their expertise in the form, we were able to only select those deemed passionate or wine savvy. We received 32 responses, 18 of which marked as savvy (people that self-assessed 3 to 5 in a competency scale up to 5).

On average, wine-savvy survey responders initially think that climate change’s impact on wine is 4.22 on a scale from 0 (not at all) to 5 (a key driver). After having watched the video, the same people report a 7% increase in perceived threat, stating that, on average, the impact of climate change is 4.50. More importantly, when asked “How willing are you to change your behaviour to ensure wine’s long term survival?”, people initially report 3.22 out of 5, while 3.61 after watching the video, an increase by 12%.

Finally, when asked whether they would donate to support a cause to ensure the long-term survival of wine, respondents report only 1.56 out of 5, while 1.83 after viewing the short piece, still remaining relatively low.

Because our data sketch is in the format of an Instagram post video and meant to be viewed by social media users, we also chose to share the video on a private Instagram profile with 117 followers to see how the video performed. In the first 24 hours, the video accrued 47 views (40%) and 10 likes (8.5%). The last 11 videos of the Now This News (2.3 million views) profile had an average of 133,840 views (5.8%). Obviously, a private Instagram has a curated list of followers compared to Now This News that are more likely to watch a video, but still a solid performance for a 1-minute video on wine and climate change.