How climate change impacts wine

By Eugenio Zuccarelli, Tyler Millis and Neil Pendse

Wine has been part of our society since the beginning of humanity. The first evidence of wine-making dates back to 6000 BC and the practice spans the millennia from prehistory to the Roman Empire, through the Renaissance, all the way to the present— and we are all thankful for that.

Wine-making has become not just like any other form of activity, but almost an art. An art that over these 700 years has become not only a pleasure for the palate but a form of alternative investment, especially in uncertain times. An art so important that we have detailed records of the grape-harvesting dates for the last 700 years.

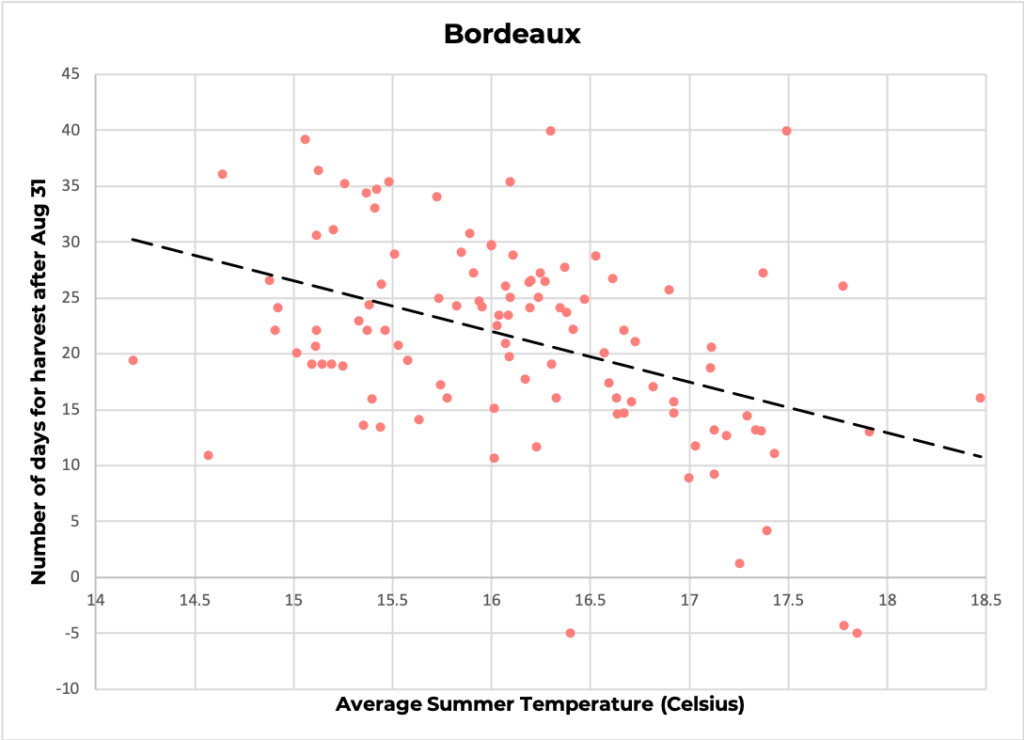

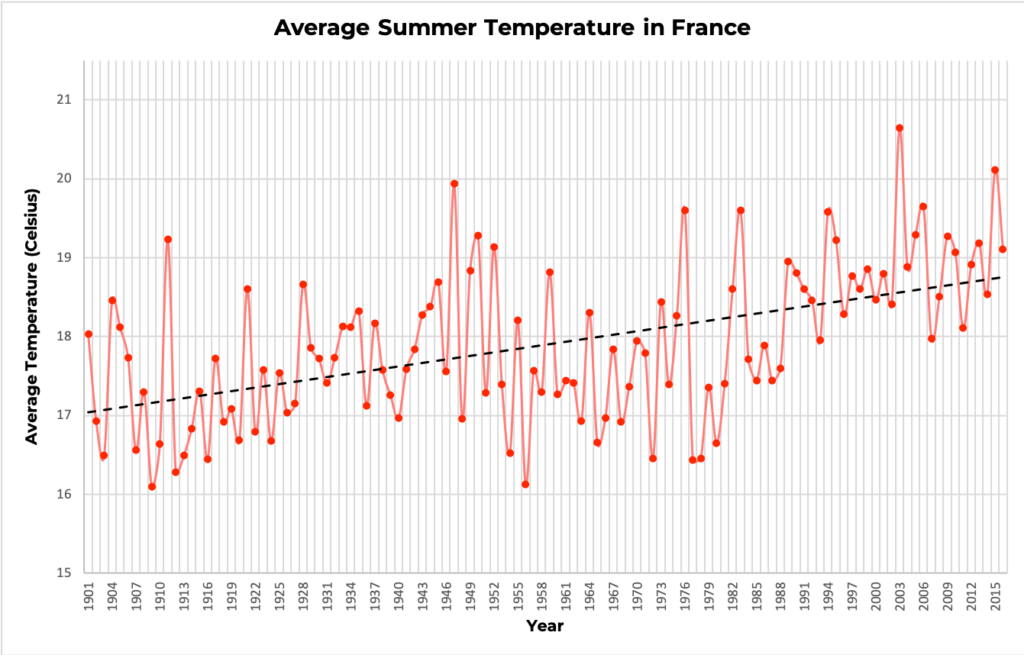

Over just the last century, however, climate change has taken a toll on wine-making. Rising temperatures have shifted the harvesting dates earlier in the year, causing the grapes to ripen faster. The harvest date is, indeed, a key element of wine-making: harvest too early and the wine will not have developed the chemicals that give each region its unique flavour; harvest too late and the grape accumulates too much sugar, making the wine more alcoholic.

Over the last centuries, temperature and harvesting dates have oscillated together in a somewhat cyclical pattern. Temperature rose between the 10th and 14th century speeding up ripening, shifting the grape harvesting dates, which fell earlier in the summer. Temperature cooled down between 1400 and 1800, in what is called the Little Ice Age, and, correspondingly, grapes took longer to mature.

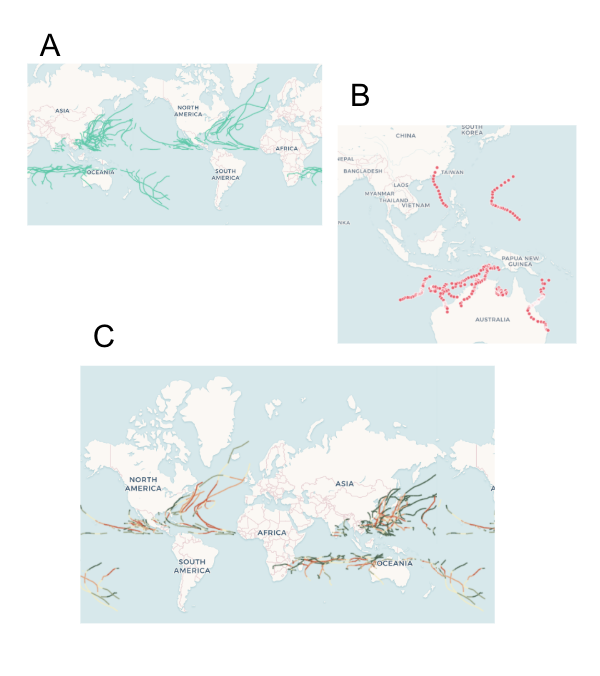

https://public.tableau.com/shared/F3BKP2B3F?:display_count=y&:origin=viz_share_link&:embed=y

Over just 100 years, climate took such a sharp increase, that grapes are now harvested almost two weeks before the historical average. Regions in the South of France have seen harvests wiped out by rising temperature. In July 2019 alone, some regions saw temperatures as high as 45.9 °C (114.6 °F). Many governments have pledged to limit temperature rise to 1.5 °C in the next thirty years, but this limited increase alone could have disastrous effects on wine production.

This not only threatens to continue to destroy vineyards themselves but also wine investors’ gains. If we do not act now, the rapidly shifting harvesting dates will irremediably change the taste of classics such as Bordeaux and Bourgogne wines, producing wine that is neither suitable to drink nor to invest, strongly damaging wine producers, connoisseurs and investors.

Who Are We: Investigative data journalists working for a magazine such as Bloomberg or The New Yorker.

Who Is Our Target Audience: Affluent people who invest in wine and have the resources to counter climate change through policy change both at the industrial and national level.

Goal: Plots of increasing temperature aren’t convincing enough for people to take action against climate change and sometimes even accept that the climate is changing. However, it has been seen that stories which people can relate to and which are backed by data have the power to convince people about a hypothesis. In this article, we are using people’s love for wine to convince them that they need to take action against climate change.

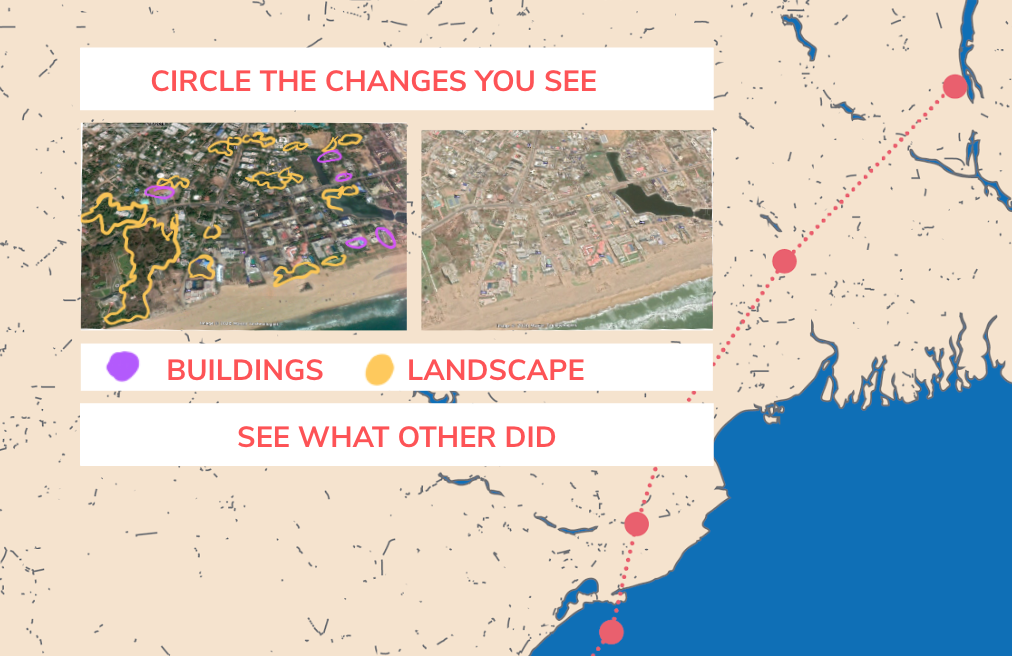

Tools Used: Static Maps, Interactive Maps (Tableau), Scatter Plots

The article can also be found here.

Datasets used:

- Western Europe 650 Year Grape Harvest Date Database

- World Bank Group climate change knowledge portal